How and why

The first land plants had no leaves. Leaves began to evolve during the Devonian as small outgrowths or by the webbing together of small branches. The first seeds also evolved – the most significant event ever for land plants.

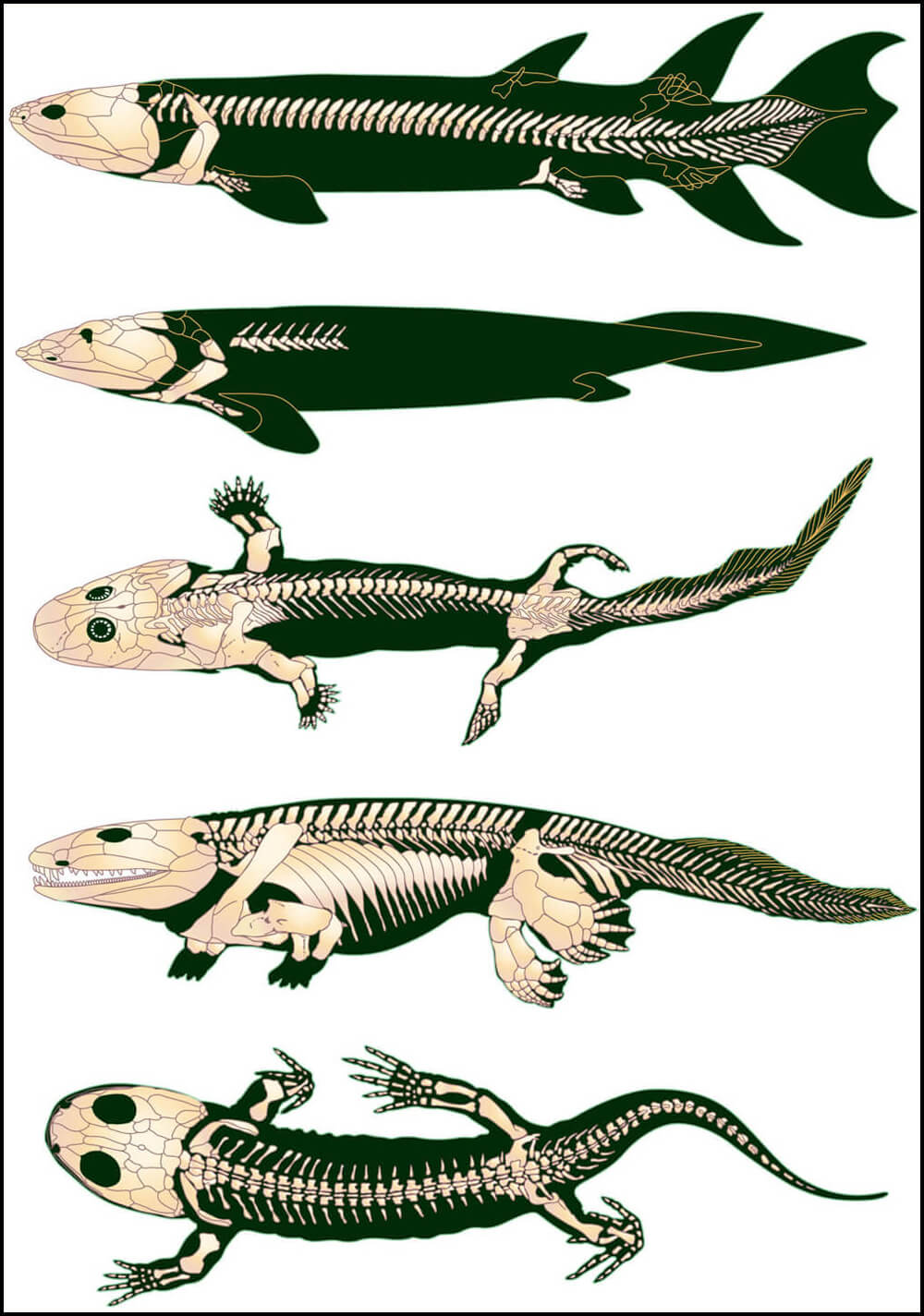

For animals, life on land required a number of new features, including support for the body, the ability to move about, protection against dehydration and the ability to breathe air. These features evolved in the first four-footed animals during the Devonian, even though they never lived on land.

Ichtyostega, an early four-footed animal. It was a large, strong predator wuth sharp jaw teeth. In spite of its limbs it propably lived most of its life in water.

Photo: Annica Roos

Leaves and seeds

The first land plants of the preceding period, the Silurian, had thin green stems without leaves. But during the Devonian, the first leaves evolved. Their surfaces captured greater amounts of energy from the sunlight for the plants.

The leaves developed from the stem, either as small outgrowths or by small branches webbing together into a larger, flat leaf.

Evolution of leaves. Small branches webbed together

into a larger leaf.

Image: Annica Roos

The development of seeds is the most significant event in the history of land plans. It occurred over 350 million years ago! Today, seed plants are the most common plants on land.

The seed enabled a new kind of reproduction which made plants less dependent on water. And since pollen and seeds can be transported by the wind, plants could also be spread over large distances, even to the inner regions of continents.

Seeds are interpreted to have evolved in the following stages:

- Separate male and female spores evolved, the male spores were smaller than the female spores. The first plants that reproduced with male and female spores were the tree-like progymnosperms

which are now extinct. - Female spores were encased in a protective capsule to form an ovule (called a seed when fertilized). There was only a small opening through which wind-borne male spores could enter, germinate to form the male gamete-producing stage, release the sperm and fertilize the female ovule.

- The male spores containing microscopic male plants evolved into pollen grains. The male pollen could be transported by wind directly to the seed to avoid the need for water in fertilization.

Animals on land

The rapid evolution of vertebrate land animals is probably due to the availability of new food sources. They could feast on arthropods such as insects, spiders and centipedes.

Vertebrate animals that could adapt to life on land could also avoid water-dwelling predators. An increasingly dry climate may have created additional pressure to adapt to life on land by reducing the number of lakes and other bodies of water.

Animals that dwell on land have a body construction that differs from their water-dwelling relatives’. Land animals do not have the support of water to bear their weight, and that required several changes in their skeletons:

- Stronger connections between the vertebrae of the spine.

- Limbs that lift the spine up from the ground, in place of pectoral and pelvic fins.

- Hips and shoulders that are able to bear the entire body weight.

- A mobile head.

These adaptations occurred in all four-footed animals of the Devonian, making them different from their ancestors, the coelacanth and sarcopterygian fish.

Changes in the bones of the fins can already be observed in coelecanth and lungfish fossils. But it was not until the first amphibians that the fins evolved into true limbs.

To prevent dehydration when breathing air, the animals need mucus membranes in the air passages. They also needed tear ducts to moisten inhaled air and prevent the eyes from drying out. These features were developed at an early stage and were already present in coelecanth fish, even though they spent their entire lives in water.

Gills are of no use for living on land. The ability to breathe air is necessary, and lungs had already evolved in some fish that continued to live in water. The sarcopterygian fish Eusthenopteron, for example, had both lungs and gills.

Gills were completely replaced by lungs in adult amphibians, but remain in the young during the tadpole stage.

The eyes of the sarcopterygian fish Panderichthys were placed on the top of its skull, which is advantageous if one lives near the surface of the water.

Photo: Tyler Rhodes

Internal nostrils and placement of the eyes on the top of the skull were two other adaptations that made it possible to live in both water and on land. Those features were already present in sarcopterygian fish, but not in coelecanths.

Eventually, land-dwelling animals also evolved thicker skin as protection against dehydration.