Then and now

Pterosaurs and bats

The flying capabilities of extinct pterosaurs and modern bats have evolved in a similar manner. The wings of both groups have been formed with thin membranes of skin stretched out with the hands.

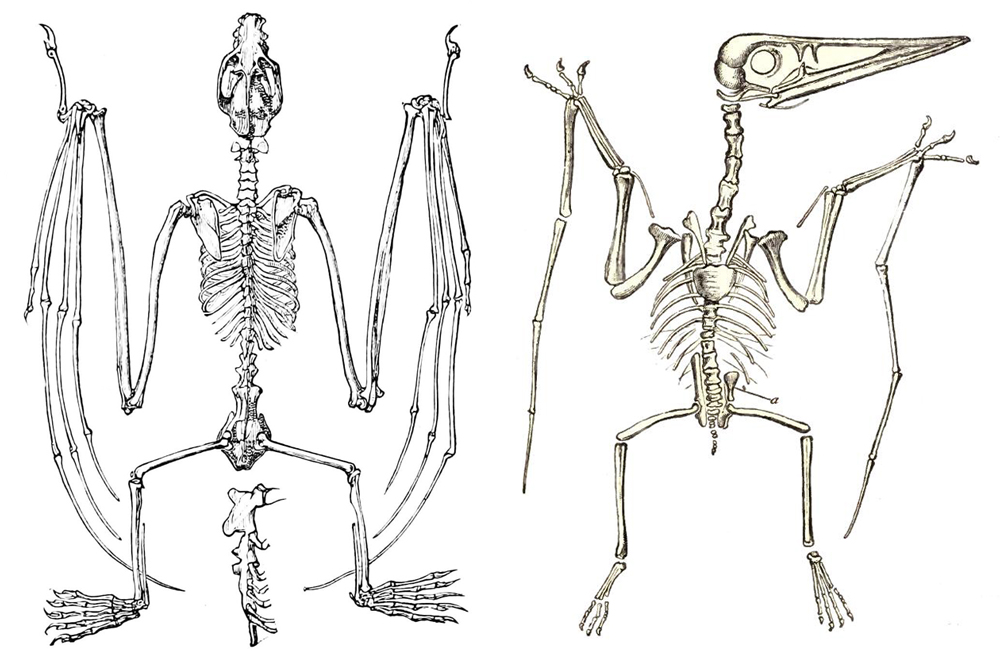

Skeleton of a modern bat, left, and of the pterosaur Pterodactylus, right.

But there are also differences. Whereas a bat’s wing is extended with all fingers of the hand, pterosaurs used only one finger for the same task. An extremely long ring finger, in combination with a small bone on the wrist, stretched out the wing.

Because the outstretched finger was so remarkably long, one of the best-known pterosaurs has been named Pterodactylus, a Greek word meaning ”finger wing”.

Flight-ready pterosaurs

That pterosaurs laid eggs is known from the fossil of such an egg discovered in China. The egg contained a nearly fully formed baby pterosaur with a wingspan of 25 centimetres. Scientists therefore conclude that it could take care of itself and was flight-ready as soon as it hatched.

In contrast, the young of bats and birds require much care before they are able to manage on their own.

We know that pterosaurs laid eggs thanks to well-preserved egg fossils from China. This egg contains a nearly fully developed kid with a wingspan of 25 centimeters.

Photo: X Wang och Z Zhou

Diurnal versus nocturnal

Another key difference is that pterosaurs were active during daylight hours – diurnal. They used their large eyes to orient themselves and find food. The majority of bats are active mainly at night, they rely on hearing and echolocation to hunt and orient themselves.

Most bat species are active at night – nocturnal. That may be due to the fact that they evolved later than birds, which are the best flyers of all vertebrates. In order to avoid competition with birds, bats became active at night when most birds are resting. Pterosaurs, however, were the first flying vertebrates and had no competitors in the skies.

Stones in the stomach

The large plant-eating dinosaurs were not able to chew their food – their teeth and jaws were too small. They gobbled up plants and swallowed them whole. But how could they break down the huge quantities of vegetation that they ate?

The solution was to swallow large stones which helped to grind up their food. Such stomach stones, called gastrolites, have been found in fossil skeletons of Plateosaurus and several other dinosaurs. They have also been found in ocean crocodiles of the Jurassic.

Fossil gastroliths. Just like today's chickens the dinosaurs swallowed stones to help grind the food that is swallowed.

Photo: Wolfgang Sauber

The same method is used by modern chickens and other seed-eating birds. Lacking teeth, they eat small stones which help them grind the food they swallow. That is why game birds such as capercaillies and grouse can be seen plucking gravel from forest roads.

Modern crocodiles are also unable to chew, and use the same method to grind food.

Youthful adults

Gherrothorax was a large amphibian of the Triassic, and you can see a model of it here. Adults retained their outer gills from the larval stage. It looked like an enormous tadpole and was adapted to living its entire life in fresh water.

Still living in Mexico is a distant relative, the axolotl, which is an endangered species.

Left, axolotln, a distant relative to Gerrothorax. Right, model of the triassic amphibian Gerrothorax.

Photo: Orizatriz, Annica Roos

Just like Gerrothorax, adult axolotls have retained some features of the larval stage, including the outer gills.

When an animal as an adult retains features of younger stages, that is called neoteny.